Supply chain. Two words that can sound like a hex when trying to run an organized business today. Every time something’s on backorder or I pay an inflated price, I’ll clench my fist and curse … supply chain. Brewers need a lot of products and ingredients to make beer, which requires a variety of supply chains operating efficiently every week of the year, which means cursing has become a second language in the craft brewing community.

The beer business is a commodity- and equipment-heavy manufacturing process, and supply chain shortages have become normal over the last three years — cans, glass, malt/barley, hops, stainless steel and domestic shipping for all those goods. Here’s another one: Carbon dioxide or CO2 is a brewing essential that has seen serious production and supply issues since the beginning of the pandemic. Because CO2 is such a versatile industrial material, it’s in high demand — especially in the summer — as it can used be to make everything from dry ice to weed. Shortages have now become a seasonal problem.

“It’s going to continue to be an issue,” confirmed Chuck Skypeck, technical brewing projects director at the Brewers Association. “Europe’s actually even worse off than us. Great Britain’s pretty much dependent on CO2 production from ammonia facilities, and their CO2 issues have really become a seasonal thing. It happens every year. I see us going down that same road. That’s my biggest talking point. This isn’t a one-off problem.”

For the foreseeable future, fluctuating CO2 supply issues and rising prices are here to stay — “We’ve heard of [price] increases up to 40 percent,” said Skypeck. In this series of five articles called The CO2 Shortage, I will help craft brewers prepare and perhaps reorganize operations to accommodate these CO2 shortfalls. We’ll discuss why there is a CO2 shortage in the first place; how CO2 is used during the brewing, packaging and serving processes; best practices for usage and supply agreements; and alternatives to buying CO2 such as CO2 recapture systems and nitrogen generators.

Of course, CO2 is not in short supply everywhere. There’s definitely a regional factor involved in its production and supply chain, and shortages seem centered around hotspots like the West Coast, Midwest and New England. I interviewed a variety of big and small craft brewers for this feature (along with multiple trade associations and equipment manufacturers). Some beer makers have seen no disruptions or price increases. Others have halted production.

“It’s the worst I’ve ever seen,” said Andrew Dickson, production manager at Tröegs Independent Brewing in Hershey, Pa. “CO2 supply is very limited right now. Recently, we shut down for three days [because of it], and we didn’t package any beer for a week. We typically package 24 hours a day, five days a week.”

That’s scary. It’s pushing some beverage alcohol makers to adapt. Massachusetts’ Night Shift Brewing made headlines earlier this year for announcing it was mostly switching to contract brewing, and one of the main factors calculated in that decision was the beverage-grade carbon dioxide shortage. That’s drastic. Other brewers are evolving their operations to fill in the gaps.

“Due to the limited supply, we’ve had to be creative,” admitted Max McKenna, senior marketing manager at Boston-based Dorchester Brewing Co. “Due to our contract, we haven’t seen a price hike from our current CO2 supplier, despite the rising prices in other parts of the market. The impact so far has been mostly around limited allocation, but we’ve had to get creative with our operations scheduling and recently introduced nitrogen where we can in the process to sip CO2 as slowly as possible to maintain supply. The CO2 shortage has absolutely affected Dorchester Brewing Co. — just as it has so many craft breweries here in New England.”

It’s the new norm for some craft breweries, so this CO2 Shortage series will help pros begin to understand how brewers and suppliers are employing best practices and clever alternatives to keep operations producing great beer for thirsty customers with minimal hiccups (at least on the manufacturing side). But before we can into all that, let’s first understand…

Why is there a CO2 shortage in the first place?

Photo credit: Vsevolod Chuvanov.

Fun fact: No one really produces commercial-grade CO2 for use in food and beverage.

Carbon dioxide for commercial use often comes from geological reserves or from the by-product gas streams of something else being produced.

Here’s an example: One of the largest sources of food- and beverage-grade CO2 is a byproduct of manufacturing ammonia. Today, roughly 80 percent of all ammonia produced is used for fertilizer production. During this process, CO2 must be removed, and it is eventually captured and refined for sale.

Well, when these ammonia and fertilizer plants shut down and/or plan maintenance — which they usually do from April to July as peak production is usually in August to March, according to this excellent article written by Calox Inc. (a California industrial gas supplier in Los Angeles) — this greatly impacts the overall supply chain of CO2. This can be one reason why CO2 can be harder to find during the summer. Another reason: CO2 is basically dry ice when frozen.

“There’s definitely increased usage due to hotter summer temperatures and CO2 source plant shutdowns, either for periodic maintenance or economic reasons. These have had a significant impact on CO2 availability,” explained Paul Pflieger, director of marketing and communications at the Compressed Gas Association.

CO2 can be captured from the production of a variety of products — not just ammonia. According to this CGA resource, CO2 can be created from ethyl alcohol, hydrogen, ethylene oxide and synthetic natural gas production (and also via other processes). It all depends on how it’s produced in your region. Watch here as Walker Modic, sustainability specialist at Bell’s Brewery, gives a savant-like breakdown of the CO2 market’s various producers, including coal mining.

Disruptions in any of these channels can affect regional availability. For example, beverage CO2 supply is heavily impacted by disruptions in oil and ethanol production. Like ammonia, ethanol makers are an important provider of CO2, capturing that gas as a byproduct to sell. But ethanol is also blended into our gasoline supply, so when fuel production dropped sharply during the pandemic when no one was driving, ethanol and CO2 production went down. CO2 prices jumped by 25 percent, according to this article on the subject. Granted, that was a while ago, so what was up with this past summer?

“There are a few main factors behind this past summer and early fall’s CO2 tightness in the United States,” said Pflieger. “First, ammonia plants were undergoing scheduled maintenance shutdowns, delayed by COVID, that kept them from producing carbon dioxide. To make matters worse, ethanol plants that went offline during the pandemic may not have resumed operations. Some still haven’t today.

“And then there’s the weather: The beverage industry accounts for roughly 14 percent of U.S. carbon dioxide usage, but every summer, demand for CO2 increases because people want more beverages — soda, beer, you name it. Additionally, more dry ice, the solid form of carbon dioxide, is used to keep things like vaccines and food cold. The record heat that we’ve been seeing in this country and around the world is making this worse. Despite these obstacles, CGA’s members worked diligently to ensure CO2 was delivered throughout the summer and fall.”

CO2 Pro Tip: Purging tanks is maybe the biggest use of CO2 in the cellar, so Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) are an important tool to conserve usage and reduce pollution. According to the Brewers Association: “A purge at 5 psig through a 1/2-in. line allowed to run for an additional 10 minutes can consume 8 lbs of CO2 or nearly a gallon of liquid CO2.” Follow those SOPs!

The transportation of CO2 can affect availability and pricing

CO2 is contained, shipped and stored in liquid, gas or solid forms, but…

“CO2 is difficult to move around,” said Skypeck. “When you’re moving CO2 from one region to another, it’s often moved as liquid under intense pressure, but you’re also moving way more than CO2. You’re moving stainless steel around, which is heavy, right? You’re paying a lot for that moving, for the weight of that tanker, not necessarily the CO2. That’s why you see a lot of variation in supply regionally because it is difficult and expensive to move around. Subsequently, you’ll see a pretty large range in price from region to region.”

Trailer and driver shortages caused even more problems for CO2 transport and delivery.

Photo credit: Cornel Putan.

For the last three years, a variety of new CO2 supply market challenges have emerged, tracing back to contamination issues, market shifts and increased demand from other products.

CO2 keeps food products cold. CO2 is required to increase the yields of cannabis plants, and we’re all smoking way more weed these days. Some CO2 production plants are also discovering contaminants in the raw gas extracted from natural sources; CO2 needs to be pretty pure for food and beverage grade usage, and a lot of breweries still filter and polish the CO2 they buy.

Pflieger did tell us “gas contamination has not been a leading factor that has led to CO2 supply tightness.” But it is definitely one of the many factors at play that continue to add up — and there are even more factors not mentioned here, especially on a regional level.

Craft brewers have no control over these factors and forces, but beer makers do have some say in securing a stable CO2 supply or finding an alternative. To find out how, you’ll need to tune into the rest of our CO2 Shortage series (all five parts will post at 12:30 p.m. EST every day this week). Tomorrow, we’ll discuss where CO2 is used in the taproom and in cellar and packaging processes.

Click here to see other CO2 Shortage articles.

The Last Word: CO2 safety is paramount

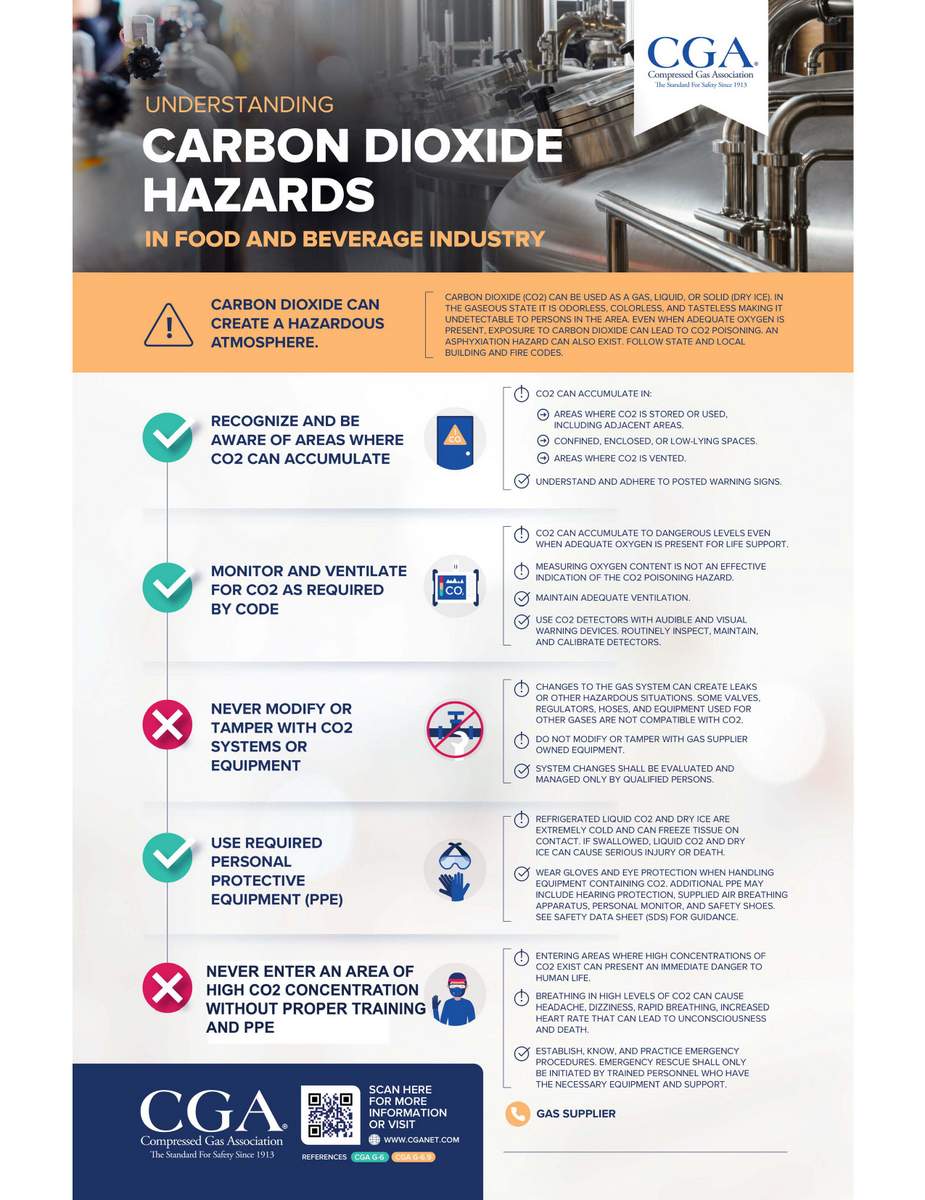

Granted, this should be the first word: Brewery employees that use, handle and work around carbon dioxide should be aware of its unique properties and potential hazards.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a colorless, odorless, faintly acidic-tasting, non-flammable gas. It’s heavier than air, so it tends to accumulate in low and confined areas — like in a brewing vessel. At high concentrations, it can cause unconsciousness, respiratory arrest and death. Accidents occur every year. CO2 can also pose other hazards — exposure to dry ice or a CO2 cylinder dropping on your feet. Frostbite, drowsiness, unconsciousness, rapid breathing, confusion and increased heart rate can all be symptoms of over exposure, according to this excellent article from Cirsa (a risk management consultant).

What are safe levels of CO2? According to that same article:

400 ppm — Outdoor fresh air contains about 400 ppm of CO2

1,000 ppm — CO2 levels indoors should ideally be below 1,000 ppm

1,500 ppm — CO2 levels above 1500 ppm indoors should be addressed with ventilation

2,000 ppm — More serious symptoms like sweating, increased heart rate and difficulty breathing can occur at CO2 levels of 2,000 ppms or more

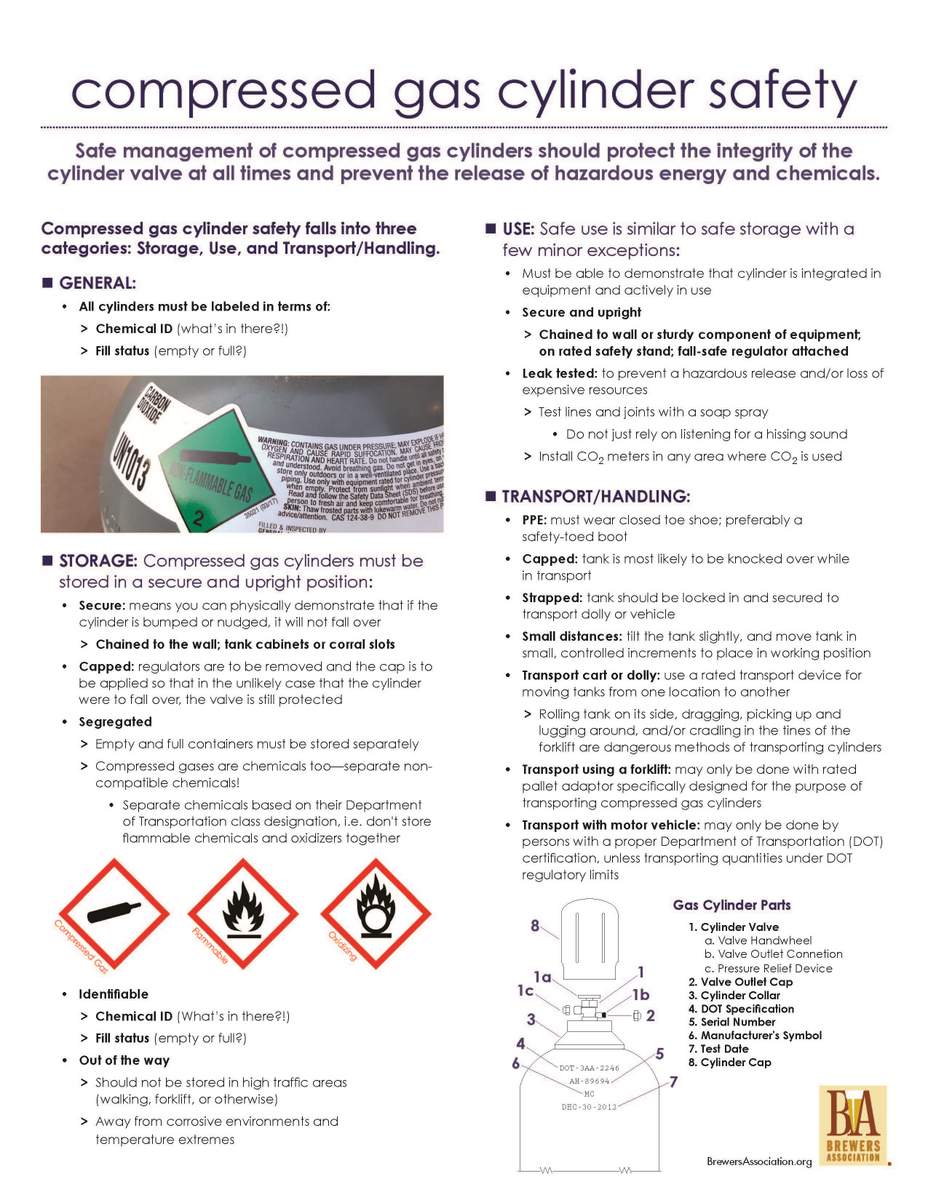

Proper ventilation, training, signage and O2/CO2 safety systems are all important factors in creating a safe working environment for your brew crew. In a brewhouse, spaces where CO2 might accumulate would be in low areas like a fermentation cellar or a walk-in cooler. Active ventilation, routinely checking for leaks and using the tried-and-true buddy system are all important aspects of a good CO2 safety plan in a brewery. Here are two other great resources — safety posters focused on CO2 dangers in food and beverage (from the Compressed Gas Association) and CO2 cylinders (from the Brewers Association).

[…] With the proliferation of breweries, supply chain issues, harvest concerns for barley and hops, a CO2 shortage, alternative beverages such as seltzer, RTD (ready-to-drink) and non-alcoholic options and cannabis […]