The December deluge. Record rain. A drought buster.

Any and all of those descriptions only begin to tell the story of what happened at Rogue Farms in December 2015. A series of winter storms rocked Northwest Oregon for weeks, dumping record amounts of rain in the Willamette Valley and heavy snow in the Cascades. Mudslides closed roads and sent houses tumbling down slopes. Storm sewers were overwhelmed and city streets turned into lakes. Rivers rose quickly and flood warnings went up along virtually every major waterway in the region.

All that rain had to go somewhere. In the valley, somewhere is the Willamette River that runs alongside Rogue Farms in Independence, Ore. Eventually, not even the river could handle all the moisture Mother Nature sent its way. On Dec. 14, the Willamette River burst out its banks and rushed into Rogue Farms. Except for a brief break, the floods cut us off from the rest of the world for two weeks.

We’ve learned to expect floods in winter. They’re part of the natural cycle of Rogue Farms. But the power of Mother Nature is awesome, unpredictable and sometimes unnerving. In the end, she gave us exactly what we needed.

Flood ready

The first Sunday in December was Mother Nature’s warning shot. A massive winter storm dropped two to three inches of rain in less than two days. A few days later the National Weather Service warned us the Willamette River was within hours of flooding. We dusted off our flood plans and got to work. Anything that could be carried away by a flood was picked up and moved to higher ground.

RELATED: The business of hops: Craft professionals share advice from farming to contracting

Tractors and trailers came in from the fields, we moved picnic tables and umbrellas from the lawn into a barn. In case you’re wondering if a flood could really wash away a heavy duty picnic table, the answer is yes. That happened here a few years back. The biggest challenge was our 7,140,289 Rogue Farms honeybees. Our Beekeeper Andrew came in on his day off to move the colonies out of the flood zone. The rest of us pitched in. One hive at time, all by hand, we moved the bees to a spot where they’d be high and dry. We’ve been here before. Years of farming on alluvial bottomland has taught us that winter floods can happen at anytime and we better be ready. As we like to say at Rogue Farms, this was not our first rodeo.

The floods in photos

By the end of the week, the Willamette River could no longer contain itself. Floodwaters poured in over Wigrich Road and flowed straight into our hopyard.

Within days, the hopyard and fields surrounding Rogue Farms were covered in water up to 4 feet deep. A neighbor who has lived in the area for decades says he’s never before seen the river rise so quickly.

The floods cut off Rogue Farms from the rest of the world for two weeks. We left behind a small crew to watch over things, but they were never in any danger. The real threat was to anyone who tried to get in or out of the farm. Wigrich Road was impassable due to high water and strong currents.

After the water receded, we returned for our first look at the damage. If you’ve never seen the power of a flood up close, it is jaw-dropping. The water rushed in with so much force that it flattened our corn and jalapeños, pulled marionberry plants out by the roots and pushed piles of compost hundreds of yards across the field.

We put on our boots and got to work

These weren’t the worst flood waters to hit Rogue Farms, but they caused the biggest mess we’ve ever seen. We sent out a call to our fellow Rogues for help with the cleanup, and they answered in droves.

We found giant logs and dead trees scattered across the hopyard. We have no idea where they came from. All we know is that they weren’t here before the floods. The ones that were too big to carry away were cut into pieces with a chain saw. You could feel the buzz everywhere on the farm.

When it was over, we went to help our neighbors. The City of Independence asked if we’d shovel some gravel and repair sidewalks that were damaged in the floods.

It was a lot of hard work. But when Rogues come together to do a job, there’s not much that can stop us from getting it done.

How the floods saved our honeybees

There’s a rule of thumb in beekeeping that you don’t check your hives in winter unless it’s absolutely necessary. Honeybees are vulnerable in cold weather. If you open the hives, even briefly, it exposes the bees to cold temperatures that may injure or even kill them.

Andrew, our beekeeper, goes to great lengths in the fall to prepare the bees for winter. He creates ventilation in the hives to remove moisture, while at the same time making sure heat doesn’t escape. He places frames so that their stores of honey are close by. Bees stay warm by huddling together in large clusters. The less they have to move away from the cluster, the better off they are. But as we carried hives out of the flood plains, Andrew sensed something was off. So he broke that rule and took a look.

It’s a good thing he did. Andrew found a surprising number of dead and dying honeybees. A recent cold spell was harder on them than anyone realized.

It’s natural for honeybees to die off in winter. For years, beekeepers knew to expect to lose about 15 percent of their colonies in cold weather, no matter how good they were at tending to their bees. For a variety of reasons, winter losses have doubled during the past decade.

We work really hard to take care of our honeybees and are proud of our program. So while these losses aren’t unusual, we were upset they happened at all. The first question we asked ourselves was, “How do we fix this?” We send our bees south in winter to pollinate an almond orchard in Northern California. Normally we’re not in a rush, but this was not a normal year. A few days after the roads were clear, Andrew arrived before sunrise to load the hives on his truck and off they went. They were gone before the rest of us arrived for work.

Winter in the almond orchards is one of the best things we do for our honeybees. The sunnier and warmer weather does wonders for them. When the almond trees start to bloom, the honeybees will spend their days flitting among the flowers and filling up on that nutritious almond pollen and nectar. When they return this spring, the honeybees will be greeted with a burst of blossoms in the next-door cherry and apple orchards. By summer, they’ll be busy pollinating our Dream Pumpkins and Prickless Marionberries. You’ll taste the rewards of their hard work the next time you try one of our meads, kolsches or braggots.

So why do we put up with this #&@!?

At times like these, someone will eventually ask us, “Why do you put up with this?” Fair question. The ground where we grow our seven hops, pumpkins, marionberries, jalapeños and garden botanicals is some of the best soil a farmer can wish for. It’s alluvial loam, a rich mixture of clay, sand and silt that was deposited here by floods.

Winter floods along the Willamette River have been a fact of life here for centuries. The Native Americans who lived on these river banks learned to adapt to its rhythms, as did the pioneer farmers who began growing hops here 150 years ago. Before then, massive Ice Age Floods filled the Willamette Valley hundreds of feet deep with rich, volcanic soil they scraped away from Eastern Washington, Idaho and Canada. The soil we farm today is the legacy of flooding that goes back 15,000 years.

Farming comes with risks, and around here one of those risks is floods. We knew that when we planted our first crop of hops at Rogue Farms nearly a decade ago. It’s because of the floods that we’re able to grow the ingredients for our beers, spirits, ciders and sodas in the kind of rich bottomland that would make most farmers jealous.

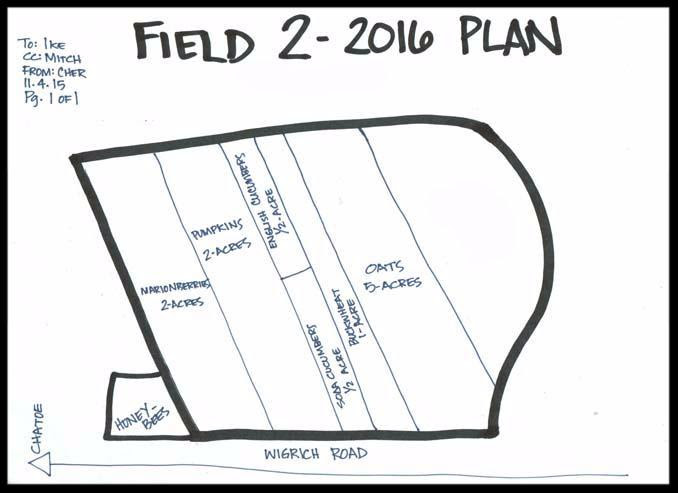

A changing proprietary palate

We’re not the types to rest on our laurels. We’re always looking for better ways to do things and that includes the proprietary palate of flavors we grow for Rogue Ales and Spirits. Last year we produced bumper crops of our McKercher Wheat, Wigrich Corn, Dream Rye and jalapeños. We have enough of these ingredients to keep our maltsters, distillers and Brewmaster John Maier busy for a long time to come. Growing more would only mean adding surplus on top of surplus.

This gives us a unique opportunity to try something new. Take oats for example. Shakespeare Oatmeal Stout is one of our oldest styles, and yet we’ve never grown our own oats. It might be time for a change. We’re also reworking our Revolution Garden, where we grow a dozen botanicals to use in our spirits, ciders and sodas. It’s also where we experiment with new crops. Our jalapeños and marionberries began as small patches in the garden.

All of this is preliminary. Nothing is set in stone or dirt. We’ll let you know what we decided in the spring version of the Crop Report.

This information was all provided from the fine folks at Rogue Ales & Spirits and the Rogue Department of Agriculture. Big ole thanks to Rogue Farms for letting us reproduce this.

Cheryl Gillson liked this on Facebook.

Anna Abatzoglou liked this on Facebook.

Beth Demmon Ivey liked this on Facebook.

RT @GP_Analytics: Weather is unpredictable – read @RogueFarms Winter Crop Report then let us forecast your hops – https://t.co/ZxWREF8zzo -…

Weather is unpredictable – read @RogueFarms Winter Crop Report then let us forecast your hops – https://t.co/ZxWREF8zzo – @CraftBrewingBiz

RT @CraftBrewingBiz: The Rogue Winter Crop Report: Learning to love the flood. Photo blog @RogueFarms @RogueSpirits https://t.co/UOGw5miW92

Rogue Winter Crop Report: Learn to love the flood https://t.co/aWkMgkD0Mf via @craftbrewingbiz

#CraftBeer #CraftBrewing #Beer #BeerBiz The Rogue Winter Crop Report: Learning to love the flood (a photo blog) https://t.co/WyO5WqgnIQ

“The Rogue Winter Crop Report: Learning to love the flood (a photo blog)” https://t.co/3m7twpcEGC