Spirits can be many things: a transcendental search, the embodiment of inspiration, a ghost in the closet, a bottle of booze. We see the spirit of America as all of the above. Before Democracy, there were spirits, and from spirits we created taverns, and it was in those taverns that we laid out the blueprint for a new kind of country, with a new kind of ideology, not ruled by kings and queens but by men and women. In other words, we got drunk and invented America.

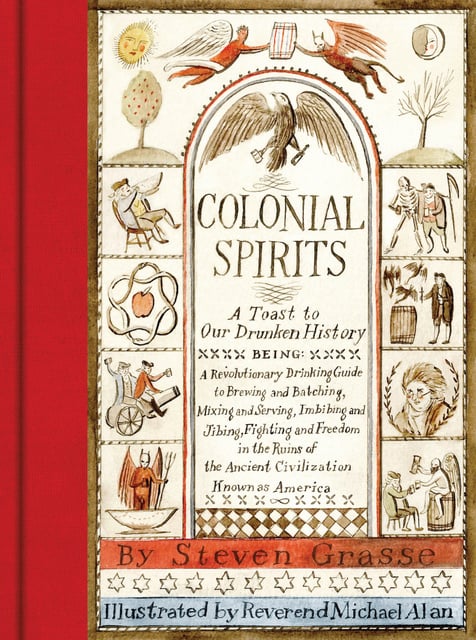

In the last few years, cocktail lovers and history buffs alike have been awash in a tide of books about the history of American mixology. But the cocktail as we know it today only came about around the time of the Industrial Revolution. So what did the first Americans drink? In Colonial Spirits: A Toast to Our Drunken History, author and spirits expert Steven Grasse — the inventive rogue behind such brands as Hendrick’s Gin, Art in The Age, Sailor Jerry and many more — does a deep, illuminating dive on the question. And what he finds is the very roots of American ingenuity, born of necessity.

Below is an awesome excerpt from his booze book, detailing the early history of American beer. We thank Grasse and Abrams Image for allowing us to publish. We suggest you buy this publication right here, right now. It comes out September 13.

Brewers wanted

We live in a time in which beer is ubiquitous. Never before have we been able to enjoy so vast a variety of beers and ales begotten by such a variety of brewers and providers, be they macro- or microbrews, or even the single batch whipped up by you and your neighbors, the humble hobbyists. But for the bloody, desperate, and glorious three hundred years of Americans before us, a wholly different age of ubiquitous beer prevailed. Although there were different varieties in evidence in every hill and dell — beers we can’t but imagine! Beers we will never know! Beers we will, by God, show you how to make here today!

“Ubiquitous beer” in colonial times was ubiquitous in that man, woman, and, yes, even child drank it all the livelong goddamned day. No sooner did we tread upon American soil in the early 1600s than what has turned into our never-ending quest for never-ending beer began. And immediately it became apparent that the settlers would have to make do with what was on hand. At Plymouth Rock, the Wampanoags taught them how to ferment alcohol, but of what use was that alone, really, if you’ve nothing to ferment?

“Ubiquitous beer” in colonial times was ubiquitous in that man, woman, and, yes, even child drank it all the livelong goddamned day. No sooner did we tread upon American soil in the early 1600s than what has turned into our never-ending quest for never-ending beer began. And immediately it became apparent that the settlers would have to make do with what was on hand. At Plymouth Rock, the Wampanoags taught them how to ferment alcohol, but of what use was that alone, really, if you’ve nothing to ferment?

For beer is made this way, if you didn’t know: First, you need a grain (most often barley, yes, but really, any old grain will do) and you need to malt that grain, only to then make a hot mash out of it. Then boil it with hops and allow the resulting “wort” to cool; strain the wort and ferment it with yeast. Next, you wait. And then you have beer.

But there was a wrench in the works for our earliest American brewers: a distinct lack of hops. Some lucky settlers did manage to find hops growing in the wild, but their supply was quickly exhausted, leaving them in the same awful situation they were in when they were dropped off by mercenary sailors here in the first place: There just wasn’t enough beer to go around. Like a college party, once the crew on the Mayflower saw that they were down to their last few barrels of ale, they cleared the ship. Heavy friends only would partake for the duration.

In Jamestown, Virginia, the situation was even worse: Somehow, the early settlers there had managed to come all the way over to the colony without thinking to bring someone who actually knew how to make beer. After knocking on every door to see if any of the settlers ever knew, or could remember, could maybe just get lucky and figure out how beer was made, they took the only option left to them: In 1609, they wrote back to London and placed ads in the local papers seeking a brewer, any brewer at all. Imagine the hero’s welcome that hearty soul received when at long last he stepped off the boat and into the grateful arms of the people of Jamestown.

Our desire for beer was, as discussed, both a born-in cultural habit as well as what was then a common-sense approach not to drink water and possibly die in any one of a myriad of unappealing ways. What the settlers could not have expected was that this appetite would not immediately be sated in what was both a bounteous and confoundingly harsh new land.

And so it was that improvisation prevailed. As one would expect, prior to the advent of taverns in America, all beer was brewed at home — there was nowhere else to do it. And in point of fact, even by the mid-1700s, when taverns lined early American streets, “private tippling houses” were still in such abundance that grand juries existed in each of the larger cities for the express purpose of ferreting them out. Speakeasies, it turned out, were in our DNA. And it would take hundreds of years for them to be beaten out of us. But that is a story for another time.

Small beer

As the early Americans broadened their efforts to accrue the variety of beers, ales and ciders they had enjoyed across the Atlantic, so too did the old social pecking order of drinks begin to manifest itself. Working men enjoyed the strongest ales; Quakers, whose teetotaling has been somewhat exaggerated by history, took cider; women and children drank something called small beer, which was itself a sort of “base beer”— small beer being the simplest beer one could make. Brewed and fermented for a much shorter time than proper beers and ales, small beer bore a lower alcohol level and not as strong a flavor. It would, to modern tastes, register as sour — but then, so would all beers of this pre-pasteurization era.

General George Washington’s Small Beer instructions

Take a large Siffer [Sifter] full of Bran Hops to your Taste. Boil these 3 hours. Then strain out 30 Gall[ons] into a cooler, put in 3 Gall[ons] Molasses while the Beer is Scalding hot or rather draw the Molasses into the cooler & St[r]ain the Beer on it while boiling Hot. Let this stand till it is little more than Blood warm. Then put in a quart of Yea[s]t if the Weather is very Cold, cover it over with a Blank[et] & let it Work in the Cooler 24 hours then put it into the Cask — leave the bung open till it is almost don[e] Working — Bottle it that Week it was Brewed. — From a notebook (c. 1757) kept by George Washington

A recipe for Stock Ale (makes 1 gallon)

Our goal here was to re-create a Colonial era-inspired beer that would be an exceptional brown ale in all the recipes contained in this book calling for brown ale. For the beginner brewer, take this recipe to your nearest homebrew store for assistance and assemble the ingredients and necessary equipment. Searching “home-brew supplies” online will also provide plenty of resources to help you get started. We were able to procure everything we needed to brew a gallon of Stock Ale for less than a hundred dollars.

For your reference: Wort is the term for unfermented beer. Trub is the term for the sludge that settles on the bottom of the stockpot or fermenter. Sanitation is extremely important when brewing. Your home-brew store will be able to set you up with proper sanitizing procedures.

Supplies:

- Stainless steel stockpot

- 2-gallon (7.5-L) fermenting bucket with stopper, air lock, and spigot (this doubles as the bottling bucket)

- Cheesecloth sack

- Kitchen thermometer with a register of at least 40° to 180°F (4 to 82°C)

- Stainless steel stirring spoon

- Siphon

- Carboy

- Bottle filler

- 12 (12-ounce/360-ml) bottles

- Bottle caps and capper

- Carb tabs

Ingredients:

- 1½ gallons (5.8 L) filtered water

- ½ cup (120 ml) molasses for baking

- 2 pounds (910 g) Maris Otter malt

- 1 packet (0.4 ounces/11.5 g) Safbrew

- 1 cup (225 g) amber malt

- S-33 yeast

- 1 ounce (30 g) Kent Goldings Hops

Sanitize all equipment prior to beginning

Instructions

Instructions

- In a large stockpot, bring the water to 170°F (75°C). Meanwhile, put the Maris Otter malt and amber malt in a cheesecloth sack, and make a knot in the sack to tie off. • Submerge the sack of malt in the hot water and steep for 2 hours, maintaining a constant temperature of 150° to 155°F (65° to 70°C). keep an eye on the temperature the entire time— a kettle of boiling water and an alternate container of cool water are useful to have on hand to keep the brew at the correct temperature.

- After 2 hours, remove the sack of malt and transfer it to a large bowl. These grains can be discarded — or, once they have cooled, measure them out by the cup and freeze for future baking projects.

- Add ¾ ounce (20 g) of the kent Goldings hops to the wort and bring to a rapid boil. Boil for 45 minutes.

- Add the molasses and boil for 15 minutes more.

- Turn off the heat, add the remaining ¼ ounce (10 g) of kent Goldings hops, and cover.

- Submerge the pot in an ice bath (a kitchen sink works well for this) and chill until the brew reaches 70°F (20°C).

- Siphon the wort into a fermenting bucket, leaving any trub in the bottom of the stockpot.

- Add the yeast to the wort, snap on the lid, and place the fermenting bucket in a room temperature area that will not be disturbed.

- Seal the bucket with a stopper and air lock.

- Allow the wort to ferment for 2 to 3 days at room temperature.

- Remove the stopper and air lock. Siphon the fermenting wort into a sanitized glass carboy, leaving any trub in the fermenting bucket. Seal the carboy with a stopper and air lock and ferment for another 7 to 10 days.

- Once the wort has fermented a second time, it is ready to bottle. Assemble and sanitize the bottles, bottle caps, siphon, bottle filler, and bottling bucket. Siphon the wort from the carboy into the bottling bucket, keeping any trub left in the carboy.

- Add 3 to 4 carb tabs to each empty bottle.

- Attach the siphon and bottle filler to the bucket spigot. Open the spigot, fill, and cap the bottles.

- Store the bottled beer at room temperature, away from light, for 1 to 3 weeks before serving.

Steven Grasse is a renaissance brand maker whose influence has made Hendrick’s gin, Art in the Age spirits, Narragansett beer, Sailor Jerry rum and Tamworth Distillery household names and darlings of the contemporary cocktail movement. As the principal of Quaker City Mercantile, which he founded in 1988, Grasse has worked with brands from MTV to Guinness, bringing a manic energy and a deep devotion to history to his work. His first book, The Evil Empire: 101 Ways England Ruined the World was a surprise smash when it debuted, and he still regularly receives calls from the BBC wanting to know just what he’s on about.

Joshua Bennett liked this on Facebook.

Amy Fischer liked this on Facebook.

Takehiko Nakahara liked this on Facebook.

Mike Keating liked this on Facebook.

Scott Tucker liked this on Facebook.

RT @CraftBrewingBiz: Colonial Spirits: A brief history of colonial-era beer. #props @ABRAMSbooks @StevenGrasse https://t.co/09DDwD0eEJ

RT @crsimp01: A brief history of colonial-era beer (including an awesome Stock Ale recipe) https://t.co/uo1gL741UO via @craftbrewingbiz

A brief history of America’s first beer makers (including an awesome Stock Ale recipe) https://t.co/jPcBLfT63c

RT @crsimp01: A brief history of colonial-era beer (including an awesome Stock Ale recipe) https://t.co/uo1gL741UO via @craftbrewingbiz

A brief history of colonial-era beer (including an awesome Stock Ale recipe) https://t.co/uo1gL741UO via @craftbrewingbiz

Corey Lord liked this on Facebook.

Colonial Spirits: A brief history of America’s first beer makers (including an awesome Stock Ale recipe): Bee… https://t.co/UTkdnEZpM2

Colonial Spirits: A brief history of America’s first beer makers (including an awesome Stock Ale recipe… https://t.co/HYhLVqsIKH #beer

RT @CraftBrewingBiz: Colonial Spirits: A brief history of colonial-era beer. #props @ABRAMSbooks @StevenGrasse https://t.co/09DDwD0eEJ

Jerry Elliott liked this on Facebook.

Jared Read liked this on Facebook.