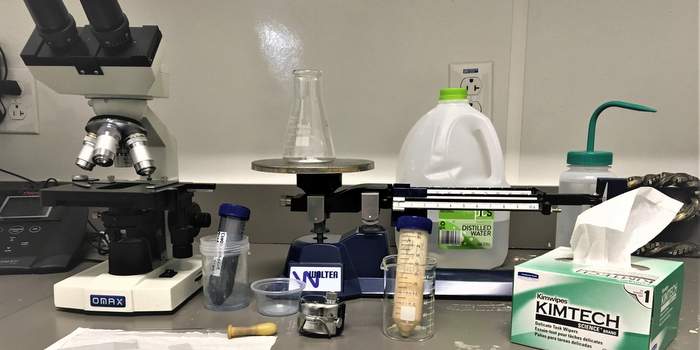

In this series of articles, Amy Todd, owner and operator of Zymology Labs, a third-party beer testing lab, who also works part-time in the lab at Zero Gravity Craft Brewery, gives us a detailed ground-floor view of the day-to-day lab routines that separate quality craft breweries from the pack.

There’s no point in taking measurements if you don’t do anything with the data. This is personally one of my biggest challenges so I try to automate as much as I can with pivot tables and charts that automatically update from my main list of results. I try to experiment with different ways to set up my data and make it work for me – both for entering data, and for analyzing it.

It can be a challenge trying to decide how to set up your data. I’ve played around with trying to keep everything together, separate, online, paper copies and have settled on a mix of a few different data sets. Usually this has to do with how I collect and enter various forms of data.

Information I collect from the alcolyzer, such as ABV, starting and final and starting gravity, real degree of fermentation, all go into one googlesheet. This file then has separate tabs to track each beer by attribute so I can quickly notice any trends or out of spec beers.

When I run IBUs, I write my results in a notebook since the instrument isn’t near my computer. The final absorbance needs to be multiplied by 50 so I have that calculation built into a separate IBU googlesheet.

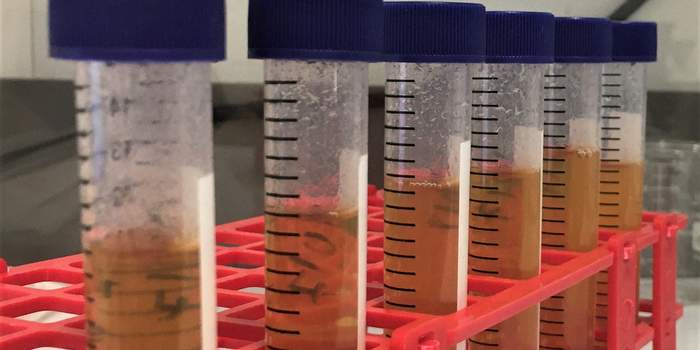

The third main file I use is one to track micro results. One tab is for HLP results, another for sterile wort results and a few more for when I test out other types of media or do any swab testing or special projects.

It can be helpful to have all your data together for when you’re trying to troubleshoot and look for relationships, but you also need your data to be easy to enter or it won’t get done. I’m testing different things at different points in fermentation so I would then need to search for a batch every time I entered results, instead of just entering like results all in a row. I tried keeping it all together and it didn’t work for me – maybe it will for you.

It can be nice to know everything is all together and you don’t have to search separate spreadsheets, but you can also run in to problems having too much data and have a hard time knowing what to look at.

Keep it simple.

Every brewery is different and will have different priorities and focus on different parts of the brewery. You can start by looking at what you want your lab and your data to do for you.

Start small and build up as you go. If you’re trying to solve a particular problem or set up specifications for your beers you might set things up differently than if you were trying to improve your yeast viability.

During special projects you could have a temporary data tracking system that shifts to sporadic checks once you’re consistently seeing the results you want.

When setting up specifications for your beers, you can start by averaging data you already have and go from there. If you don’t have enough data yet, start by basing it off of calculated values and adjust as you get more information. Keep in mind that calculated values aren’t always the same as measured values. Determine what testing parameters you’re most interested in and if it’s something you can’t test for yet, try a 3rd party lab.

Once you have a baseline or average of where you want your beers to be you need to determine an acceptable range for your results to fall into. Some of these might be based off of preference or style, such as CO2 level, or industry standards, such as 30-60 ppb of dissolved oxygen in cans.

You don’t want your specification to be too tight where it’s impossible or very difficult to fall into your own specifications. If your CO2 spec is 2.55-2.65 and you release a beer that’s 2.67, there’s no point in having that spec. You don’t want to be lenient on one spec but rigid on another. It’s confusing. Reduce your CO2 or change your spec.

Caution range notes

Including a caution range where something is still be passable but outside of your ideal spec avoids passing something that’s “close enough.” Your hard cut off for CO2 could be 2.75 or even 2.7 with your ideal at 2.55 2.65. Then if you get a few at 2.67 where the deviation isn’t drastic enough to affects flavor quality or consistency you can still pass that beer. When something falls into this range, that can be a trigger to fill out a Root Cause Analysis sheet or look into why that beer ended up with a higher than ideal CO2 level. Make a note of what you can do next time to make sure it falls in the ideal range.

Outside of this caution range you might have a level where beers need additional processing, to be blended back into spec, or in some cases diverted from going out to market if they don’t meet your quality standards.

The value of weekly updates

It’s not very helpful to anyone else if I keep all my results to myself. It can be easy to hide in the lab and the rest of the brewery might not have any idea what you do in there all day. Often you’re testing the same things and getting the same results over and over. It can feel like there’s no point in reporting these results but remember, boring is good. Consistent results mean consistent beer, most of the time.

In an effort to start communicating results in a more consistent way and make sure I’m actually leaving time to review results instead of just take measurements, I started writing a weekly update to our head brewer and brewing director.

Every Friday (well, I try for every Friday), I send a weekly update from the lab highlighting the good, the bad and the boring. This includes a section on ABV, IBU and extract data of the beers packaged that week, a list of any out of spec beers, a summary of the beers we had at taste, dissolved oxygen summary, instrument cleaning and calibration updates, micro updates and additional notes which include special projects or lab activities that aren’t performed on a daily or weekly basis.

Beers packaged this week: I review the schedule for the week and make a list of all the beers, including batch number and tank that were canned or kegged that week. I fill in the ABV, starting and final gravity, real degree of fermentation, calories and IBUs for each batch. This give a quick snapshot of how the most recent beers performed.

Here’s an example:

| Tank | Beer | Batch | ABV | OG | Ea | Er | RDF | Calories | IBUs |

| BT4 | BB | 8 | 5.88 | 14.14 | 3.26 | 5.35 | 63.9 | 189 | 45 |

| BT3 | RD | 22 | 5.35 | 11.38 | 1.24 | 3.19 | 73.2 | 147 | 25.5 |

| BT2 | CPO | 3 | 8.02 | 17.99 | 3.42 | 6.03 | 68.5 | 242 | 64.5 |

Out of spec beers: When I’m pulling this data I also update charts of ABV, OG, Ea, and RDF for each brand. This allows me to look at fermentation trends for each beer. Sometimes a beer might be on the low end for starting gravity but the alcohol comes in right where we expect it to. Everything could still be in spec but starting to trend towards going out of spec. If something looks like it’s trending out of spec I want to know as soon as possible. Looking at a single data point I might not notice but when I put it all together in a chart like the one below it’s easier to see.

Anything out of spec would be communicated right away in a separate email but here it’s presented as a recap or a note for anything to keep a close eye on.

Some specs are internally set and based off industry standards of what we have determined are both accessible to us and within which flavor consistency isn’t affected. Some specs are set by the TTB such as alcohol content. Since we choose to include the ABV on our labels, we are required to be within +/-0.3% of what we state on the label and thus we use that as our spec. https://www.ttb.gov/beer/beverage-alcohol-manual

Taste: We hold taste panel twice a week and I list what beers we had that week and anything out of the ordinary or really positive comments. If I introduce a spike or an aged samples I’ll note that here and if participants were able to pick up on that deviation. Any additional trainings will be noted here as well.

DO: Dissolved oxygen is tested in the fermenter, bright tank, and throughout packaging. As the day goes on hoses and clamps can loosen and DO levels can change so it’s important to test throughout the day. When the folks on the canning line measure the DO in cans they fill out a spread sheet including the date, time, batch, DO level on the bright tank, and the fill head of the can they’re testing. I’ll do a quick review of this sheet and include a rough average of DO levels. If there are any spikes I’ll make note of that.

Calibration and cleaning: Your results are only as good as the instruments you use so we make sure everything is working properly. The pH meter gets a daily calibration so that isn’t noted but every time I calibrate the DO meter or need to replace any parts I will note that here. We calibrate our hydrometers before use with the alcolyzer and if one needs to be replaced I’ll note that here.

Micro: This is a no news is good news kind of section unless I’m trialing some new media or working on a project. I take a mix of samples from the fermenter, bright tank, and package, incubated and refrigerated.

Additional Notes: This is my catchall for anything else going on in the lab. If I’m trialing a new method or we’re testing out a brewery upgrade that would go here. SOP updates or changes, special projects, outside lab testing, any questions or suggestions I have would all go here.

This isn’t the only way to look at data, and far from the best. This is what’s currently working for me. I’m always looking for ways to better collect, analyze and communicate data.

How do you organize and track your lab data?

Amy Todd is the Owner and Analyst for Zymology Labs as well as a lab manager for Zero Gravity Craft Brewery in Burlington, Vt.

A day in the lab series recap:

- Part 1: Sampling

- Part 2: Understanding HLP Tubes

- Part 3: Sensory panel setup, tasting tips and the triangle test

- Part 4: Updating your standard operating procedures

- Part 5: In-depth guide for cell counting

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.