Oregon State University brewing researchers and a team of bioengineers have shown that a genetically modified yeast strain can alter the fermentation process to create beers with significantly more pronounced hop aromas.

“These findings could be extremely useful in creating new beer flavors and increasing the number of tools brewers have at their disposal for producing beers with strong and varied tropical flavors and aromas,” said Tom Shellhammer, the Nor’Wester Professor of Fermentation Science at Oregon State.

The findings also demonstrate how synthetic biology can help protect industries and consumers from the effects of climate change, said Jeremy Roop, a co-author of the paper and a bioengineer with Berkeley Yeast, a company that develops yeast strains with enhanced fermentation traits.

“As droughts and wildfires have begun to damage the harvests of hops and other beer flavoring ingredients, engineered yeast offers a means to create these flavors in a way that is not affected by unpredictable climate events,” Roop said. “They also allow brewers to utilize a fuller potential of aroma from hops thereby increasing the sustainability of both the hop growing and brewing processes.”

The findings were recently published in the journal Fermentation. Over the past two decades, craft beer production in the United States has grown tremendously, with increasing demand from consumers for hop-forward beer styles, such as India pale ales, that express strong tropical and fruity flavors.

Hop-forward beers are typically achieved by adding large amounts of aromatic hops, with the essential oils in hops being the main contributor to aromas in beers. Many compounds are present in the essential oils, including thiols, which provide tropical aromas to beer.

But thiol content can significantly vary among hop varieties and different harvests. Also, a significant portion of the thiols found in hops are bound to other molecules thereby making them nonaromatic precursors. These new genetically modified yeast are designed to tap into the reservoir of aroma precursors and increase the amounts of free thiols, those that provide aromas brewers are seeking, in the finished beer.

Shellhammer, working with Richard Molitor, a former Oregon State graduate student now working at Boston Beer Co., and a team of scientists at Berkeley Yeast set out to boost the concentrations of tropical flavored thiol molecules in beer, and to do it in a way that wouldn’t require brewers to use additional hops.

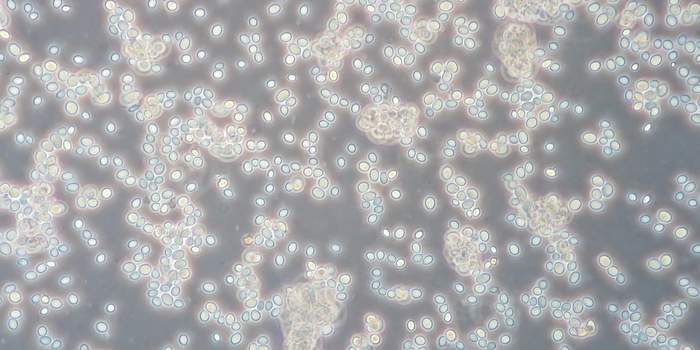

To accomplish this, the team genetically modified a brewers yeast strain to express an enzyme that increases the amount of two tropical flavored thiols produced during beer fermentation. This enzyme works by converting thiol precursor molecules, which are flavorless but abundant in hops and barley, into the volatile thiol molecules 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol (3MH) and 3-mercaptohexyl acetate (3MHA). These two molecules are found in many tropical fruits, like guava and passionfruit, and impart strong tropical flavors.

The Oregon State researchers brewed batches of beer using four versions of the genetically modified yeast strain and a conventional, unmodified version of the yeast. The genetically modified strains produced beer that had up to 73-fold and 8-fold higher 3MH and 3MHA concentrations than the parent, unmodified yeast strain

“When I was tasting these beers my eyes popped out of my head,” Shellhammer said. “This really represents a quantum shift, not just an incremental shift, in terms of the expression of these strong flavors.”

The beers brewed with the genetically modified stains were described as intensely tropical and fruity, and were associated with guava, passionfruit, mango and pineapple aromas. The researchers also noted that the yeast strains didn’t create any off flavors or affect the fermentation process in any negative way.

The yeast strains used for the research are already being used by more than 100 breweries in the United States, Roop said. Part of the appeal to brewers, he said, is that hops are expensive and also vulnerable to climate change because they require significant amounts of water and are sensitive to drought.

“The genetically modified yeast strains provide brewers an alternative means to produce tropical fruit flavor without relying on large amounts of hops,” Roop said. “This also translates to greater consistency in the brewing process.”

The new strains are not meant as replacements for hops, instead they offer brewers a new tool for producing interesting and distinctive beers while also improving the sustainability of the entire brewing supply chain, Shellhammer said.

Other co-authors of the paper are Charles Denby, Charles Depew, Daniel Liu and Sara Stadulis, all of Berkeley Yeast. The research was supported by funds from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Sean Nealon is the news editor at Oregon State University.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.