Founder of Lewis & Clark Brewing Co. Max Pigman never imagined that 15 years after he started brewing beer commercially in the basement of a restaurant in Helena that he would someday own a fully automated 60-barrel, four-vessel brewhouse serving all of Montana with his primary, seasonal and limited-edition craft beers. Since its founding in 2002, Helena, Mont.’s Lewis & Clark Brewing grew through long hours of trial and error perfecting their brands including Miner’s Gold Hefeweizen and Prickly Pear Pale Ale, knocking on distributor doors, and reaching important milestones, including multiple awards from the Great American Beer Festival and the World Beer Cup. In 2011, Lewis & Clark moved to a 130-year-old complex of historic buildings for use as a brewpub and a two-vessel, 20-barrel manually operated brewhouse and packaging facility to support its growth.

Pigman did wonder though whether the art of craft beer production would suffer when a new $9 million automated brewhouse and canning line went into production. He needn’t have worried. Pigman and his team discovered that state-of-the-art automation gave the craft brewery greater real-time information, insight into the process and additional control over the process to:

- Ensure consistency for core and seasonal beers

- Boost shelf life by at least a month

- Reduce ingredient costs

- Increase output so that every distributor request for product could be fulfilled

- Give the brewery greater agility to respond to market demands

- Improve worker safety

The year 2011 also brought a shift from bottles to cans with the addition of a 25-can-per-minute filling line. Summer and associated outdoor activities are the prime beer consumption months in Montana where the preferred beer packaging is cans. Bottles are banned from many environmentally sensitive areas. Demand for canned beer helped fuel additional growth at the brewery.

Demand leads to a leap of faith

When Lewis & Clark took over the historic complex of buildings and began brewing in the manually operated 20-barrel brewhouse, Pigman thought his business would never fill all the space available. With an annual growth of about 30 percent for five years, the brewery expanded from 1,500 barrels annually to more than 9,000, driving the need for more production capabilities and space. Pigman began the process of finding an economically feasible solution for expansion, which included evaluating properties in the greater Helena area. Luckily, the property next to his brewery became available. Gaining that parcel and obtaining a permit from the city to close a dead-end street between the adjacent properties required time and diligent effort.

Pigman persevered and eventually built a single street-spanning building connecting new and old for a proposed four-vessel 60-barrel automated brewhouse. He also planned for an expanded filling operation which eventually took shape as a 250-can-per-minute line featuring a state-of-the-art Krones filler. Always looking forward, the building is constructed in such a way that it will be easy to drop in 300-barrel fermenters should Lewis & Clark’s demand grow to require that level of production.

Key partners engage with the project

For the implementation of the new brewhouse, Pigman called on the services of Providence Process Solutions, Melbourne, Fla., a company dedicated to the design and building of craft beer and distilled spirits plants from 30 to 200-barrels in size.

“We explained to Max that Providence Process Solutions has a three-phase approach to design and build,” said Vernon Spaulding, Providence Process Solutions’ president. “Phase One is the development of a complete set of financial and market data to determine whether the upgrade makes sense financially. In the case of Lewis & Clark, the upgrade was certainly needed if the company wanted to continue to grow and the numbers support this plan. Phase Two involves architectural, mechanical, electrical and plumbing design, as well as process, equipment selection and process equipment piping design. In Phase Three, we go on-site for project management of construction and training. Typically, a new brewhouse requires anywhere from 10 to 17 months and can extend to about two years for large projects like the automated brewhouse at Lewis & Clark, where permitting and acquisition of equipment turned out to be longer lead-time activities than anticipated.”

Providence Process Solutions has more than 25 preferred partner firms that take responsibility for providing essential equipment and services. One of Providence’s key partners is Stone Technologies Inc., a nationwide system integration company with expertise in batching, process control and manufacturing operations management (MOM) systems for breweries and other process-related industries.

“Stone Technologies does everything on the process side of the brewery from designing for automated grain handling, through the brewhouse and cellar to packaging,” said Ryan Williams, Project Manager. “In other words, our team provides design and integration of all the hot process — the brew process — and on the cold side fermentation, maturation and filtration as well as integration in filling and packaging.”

New technology speeds up installation and makes for easier troubleshooting

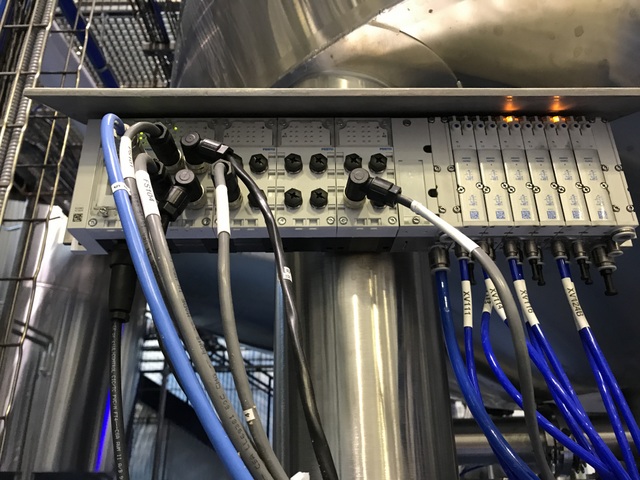

Williams saw an opportunity at Lewis & Clark to speed up installation and lower total installed costs. With the large number of automated valves, rather than running massive bundles comprised of hundreds of compressed air hoses, as well as sensor, power and communication cables, from every valve through the brewhouse to a centralized control panel in the new brewhouse’s control room, he suggested utilizing an advanced communications and control technology from automation supplier Festo. This technology reduced the hundreds of cables down to a total of 10 — five Ethernet cables and five power lines — running from the five equipment skids to the control panel.

Ryan explained to Pigman and Spaulding that the brew kettle, lauter tun, hot liquor, mash mixer and whirlpool skids would be served by a single Festo CPX control assembly of solenoid valves and discrete and analog inputs and outputs (I/O) on each vessel. Each assembly would be mounted without the need of an expensive closed control panel under grated walkways adjacent to each skid. Compressed air lines to the automated valve assemblies and I/O cabling from the sensors on each skid would be routed to the CPX unit. Then only two cables per skid would need to be routed back to the utility room housing the control panel and the Allen-Bradley ControlLogix brewhouse controller.

Fewer cables meant faster installation and less room for potential wiring errors during installation. Williams estimates that the time to wire the system took 30 to 40 percent less time with CPX assemblies than it would have without them. Shorter runs of compressed air lines to the automated valves lowers overall energy consumption. Fewer lines allows faster troubleshooting during operation. In addition to the installation savings, the brewhouse has less clutter and is easier to keep clean, an attribute that Pigman wanted for his showplace brewhouse.

Each Festo CPX assembly automates the opening and closing of ball and butterfly valves via compressed air actuation and communicates data from discrete and analog sensors involved with flow, pressure and temperature to the Allen-Bradley controller.

“I believe the CPX system is perfectly suited for skid-based systems like the ones in the Lewis & Clark brewhouse with clusters of I/O,” Williams said. “The industry is going in this direction, especially with Ethernet communications and the diagnostics inherent with modern I/O systems.”

The art and science of craft beer alive and well

In 2017, after more than two years of planning, permitting, design and construction, Spaulding and his team of partners began a series of system tests. First cold water was run through the system and then hot.

“We focused on runs where the brewmasters and their teams had safe, monitored hands-on training through the Providence Solutions’ Enterprise Brew supervisory and control human machine interface [HMI],” said Spaulding. “Working with the HMI we showed them how to open and close valves and monitor flow and temperature. We had them run a batch of grist and created a batch of wort. With the next recipe, we nailed it.”

Spaulding described the operation of Enterprise Brew with an example. “The brewmaster creates a recipe utilizing Enterprise Brew,” Spaulding explained. “Recipes are simply a sequence of steps that the system will automatically perform within the parameters of time, pressure and flow associated with each sequence. For example, when you’re mashing in, there is a specific strike temperature that the brewmaster wants to achieve. When Lewis & Clark is running Miners Gold versus Prickly Pear or Back Country Scottish-style ale, Enterprise Brew automatically knows that it is running Miners Gold, therefore the strike temperature is a specific recipe temperature target. The program automatically adjusts and modulates the volume and rate of mixing the hot liquor tank water with charcoal-filtered city water to achieve the temperature required.”

The Lewis & Clark brewhouse team soon found that the precision of the automated system led to greater control over the brewing process, a process that can require over 100 precisely defined sequences per batch. Where before variation in manual operation may have required adding more of one ingredient or changing time and temperature of a process step, the team began to use precision control to streamline the process and to optimize ingredient usage. Pigman saw the material costs decrease while consistency between batches increased. Shelf life went up by at least a month, if not more, thanks to the new centrifuge that lowered oxygen content. The new system reduces the opportunity for operator error and improves worker safety.

“With our new system, the brewmaster selects a recipe and from that point on, the brewing process is automated and consistent,” said Pigman. By way of example, he noted that, “The system automatically pulls the exact amount of malted barley from one silo and then switches over to another silo and pulls in the correct poundage of malted wheat. At the correct time, the operator screen prompts the crew to add the two bags of black barley that’s needed for a recipe. It’s an amazing system.”

Pigman said that one of the big surprises about the new brewhouse was that the brew team gained greater insight into the brewing process and the impact various steps have on consistency.

“We are now transferring new insights on processes back to our 20-barrel manual brewhouse where we are launching the new Lewis & Clark Expedition Series of limited edition beers,” Pigman said. “I don’t think there is anything artful or evocative of craft-beer romance in manually opening and closing valves or pulling grain out of a vessel when those operations can be automated. I do believe strongly that the art of brewing comes from understanding the process well enough that the brewmaster can quickly and accurately create the beer he or she wants, refining the brewing process to a razor edge of perfection day in and day out. Our new automated brewhouse provides our brew teams with tools to practice their art.”

Sean Tobin, head brewer, Lewis & Clark Brewing Co. has more than 25 years’ experience in the craft brewing industry. Tobin joined Lewis & Clark in 2010 and is most proud of his contributions to the development of the company’s numerous award-winning brews.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.